10 Films, 10 Countries, 10 Days 2: Electric Boogaloo

- Lydia Smith

- Jan 11, 2021

- 21 min read

Updated: Oct 26, 2022

I enjoyed my last 10/10/10 challenge so much that I thought I'd make a part 2 to start off 2021. Here are ten more films from ten more countries from ten more days.

Woman at War (2018)

Country: Iceland

Director: Benedikt Erlingsson

As fierce as its title, this 2018 Icelandic film is bold, eccentric, and thoroughly engrossing. Halldóra Geirharðsdóttir is Halla, a middle-aged choir conductor turned environmental vigilante who wreaks havoc on a pollutant aluminium company that threatens the natural beauty of the land. It’s a foreboding story of a woman warrior, forced to make a choice between her passion and her purpose, her loneliness serving as both her asset and her downfall. In a film where the environment is its own character, the on-location shooting and elegant cinematography play no small part in its feat as both a folkloric tale and a genuine warning. It’s not quite futuristic, and it’s not quite modern-day. Who’s to say that Iceland doesn’t have a bit of magic in its land that gives the movie its distinct aura?

The key quirk lies in the absurdist nature of the film- Halla has an identical and all-too-convenient twin sister (also played by Geirharðsdóttir), the sheer vivacity of a 40 something year old woman shooting a bow and arrow and tackling drones in the green hills inspires awe, and, perhaps my favorite element, a live band (composed of a drummer, a tubist, and an accordionist) appears at each time Halla has a very near or present danger, playing her off the scene as she approaches her uncertain fate.

In an interview between The Moveable Fest and the director-actress duo, Erlingsson addressed the live band as a “challenge to make the score before [filming].” Geirharðsdóttir, accustomed to the pit orchestra of live performances, said “...for me, it was great because in the theater, we often have the band offstage so I could work with the rhythm. And I really looked at the band like part of me being in the film. It’s like the band was part of the character," (Source 1).

It is strange and daring in the best possible way, an unorthodox apocalypse that seems both nigh and perfectly inconceivable.

But the crisis is real. In an interview with Lulu Garcia-Navarro at NPR, Geirharosodottir gave some insight to the environmental conflict at hand. “In Iceland, we have the biggest untouched highlands in Europe. So - and I think nature is as honorable as a child. So us, as adults, we have to protect nature just like we protect children because nature cannot defend itself… It is a big debate we have there because, of course, big industries and people that believe in the - making fast money, they don't agree. They say we have to use what we have and sell energy," (Source 2).

Regarding finding the humor in climate change, Geirharosdottir gave a very insightful explanation.

“What I love the way the director does it is - and what you don't realize as an American audience is that all authority in the film is played by comedian actors in Iceland. So the president is a comedian. The prime minister is a comedian. The policemen, both men and women, are comedians. So he really makes the authorities into clowns. So this is like an extra layer for Icelandic audience. But I really think as an actor - and I've done lot of comedy. And my strength has mostly been, like, comedy acting. If you do good comedy, you really open up the audience. And then you can send in the true message because when people are laughing, they actually open more up."

The superb Woman at War is on Hulu. Check it out and let me know what you think!

Dhalinyaro (Youth) (2018)

Director: Lulu Ali Ismail

Country: Djibouti

This is Djibouti’s first feature film- and it was directed by a woman! As I learn more about the East African film scene, I have found a great appreciation for films from filmmakers who are building their industry from the ground up, and I think it’s very important to recognize what a huge feat this is.

Dhalinyaro is the story of three girls from different social backgrounds who navigate their academic and personal lives at the end of their senior year. Marking a lot of universal tropes but doing so with a fresh lens is the key to this film’s success, along with the earnestness of its endearing three leads. The standout, whom I believe to be Amina Mohamed Ali as Deka, is a true revelation of combined energy and wit. Her strong screen presence convinces me of her aptitude for even more exciting roles in the future. Further, her ultimate university decision at the end of the film is what seems to ground this movie, in a very admirable act of practicality and self-knowing.

In an interview with Ciku Kimeria at OkayAfrica, Ismail shared her inspiration for the film.

“I wanted to talk about youth. It's a theme that's been made into movies in many places round the world, but not in Djibouti. I wanted to explore both what they have in common with youth elsewhere, but what makes them unique… From the beginning, it was clear to me that Djibouti was going to the fourth character in the story. I wanted to show Djibouti in a natural way—focus on the day to day life. Djibouti isn't just a harbor, it's a country, it's a city, it's a place that is developing where the youth are connected to the youth around the world and are part of a shared humanity."

She cast her stars by traveling to high schools and seeing about 300 different girls before picking her three principal actresses. As for being the spark for the film industry in her country, she said this: “The country has a lot of young, talented youth including those studying film at the university and the future of this industry can be bright. Recently an institute was set up in the country to develop the movie industry and tap into these talented youth.”

Although Ismail has yet to make a movie since, her current title as “the first lady of the Djibouti cinema” is unlikely to be tarnished anytime soon. Her message is this: “I want this film to be seen all over the world. This is my dream for all films and particularly African films. I want to see our films getting distributed widely as films.”

This lovely and truthful film is available to stream on Amazon Prime. Do your part to support the rise of the Djibouti film industry and give it some love!

Marlina the Murderer in Four Acts (2017)

Director: Mouly Surya

Country: Indonesia

TW: sexual violence

This film doesn’t exactly go down easy. In full transparency, I have always struggled with the western genre- especially those that are relentlessly savage. Now, that is by no means a demerit to the director, as a female lens did significantly calm my concerns about excessive brutality, but it should be noted that I had a tricky time making it through this one. Regardless, that should not dissuade you if you are A) a fan of spaghetti westerns, or B) the type to find comeuppance greatly satisfying, if you wish to watch this movie.

Thus, the story must be told: a widow (Marsha Timothy), after killing her rapist and his gang, heads off to find justice. Along the way, she comes across a nearly 10 month pregnant woman (Dea Panendra) seeking her husband. There is a lot to admire in the film’s style: it beautifully captures the desert heat of the island of Sumba, Panendra’s character offers an odd infusion of humor to the traditionally stale mood, and Marsha Timothy’s performance is stoic and valiant, reminiscent of a crane. The movie is arranged into four acts, the first and fourth of which are successfully severe, the second and third serving as the “journey between.” Danger is consistently met with apathy by authorities and bystanders, putting even more pressure onto Marlina herself as she serves as the sole protector and voice of good in a contained world of infinite enemies.

The film’s release happened to coincide with Hollywood’s MeToo movement, giving a feminist revenge flick its political context to soar. Director Surya thought that especially convenient given Indonesia’s own patriarchal society. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, she noted,

“You probably notice in the film that women are always entering the house and exiting from the kitchen instead of from the front door. When you go to some traditional villages like this you would see that the women would gather at the back of the house; whereas, the men would gather at the front of the house...People in this village probably don’t know what feminism is.”

She emphasized, this time to TheWrap, “We are decades behind in terms of speaking up about this kind of crime. If you’re on this island, you have to keep a weapon somewhere. It’s the Wild Wild East.”

When asked by Beatrice Verhoeven at TheWrap if she would like to have Clint Eastwood see her movie, in its various nods to the genre he played a great part in defining and the film’s new subcategory as “Satay Western, she said “I would love to be there to see that.”

As to her ultimate goal with the movie, she explained,

“Women helping each other and supporting each other, that’s what I really wanted to convey because women supporting each other is the most beautiful relationship you can have.”

It is in that comfort that one can come to appreciate Marlina the Murderer- and frankly, I do a great deal more after reading up on Souly’s approach. The film is available on Amazon Prime, and her other two earlier features, What They Don’t Talk About When They Talk About Love and Fiction. can be found for rent elsewhere.

Sources:

Wajib (2017)

Director: Annemarie Jacir

Country: Palestine

Already our third female director! Wajib is the story of a Palestinian man who comes home to help his father distribute wedding invitations for his sister per custom after having spent the last several years in Italy. New and old world collide as the two men reconcile their differences on this part road trip, part hometown-rediscovery journey that puts them at constant odds. The best aspect of this movie is its relaxed, simplistic narrative that allows the dialogue to flow at a naturalistic pace. Undoubtedly, for grown-up children and their parents, this will conjure up visceral reality as they contemplate whether to stand their ground or succumb to the influence of their loved ones. It exceeds expectations in delicately balancing the political and personal conflicts they battle, and arrives dutifully at its natural stopping point in a short ninety minutes.

In an interview with 4:3 Film at Locarno Film Festival, writer Jeremy Elphick dug into the crux of the film with director Jacir.

“I was interested in [the city of Nazareth and the custom to drop off wedding invitations], and then what it means for a father and son if Shadi has to come back to help his father… That’s his duty... But when was the last time those two were really together? I mean, and the fact that men maybe don’t talk. You know, the stereotype, they don’t talk to each other as much.” She elaborated: “It’s also a case of two men who made different choices in their lives. Different choices of how they want to live and who they want to be. They have a lot of love for each other, but at the same time, they can’t stand each other… In the end, I think it’s really about respect. What they really want from one another is some kind of basic respect.”

Jacir admitted to making both father and son equally flawed so the audience isn’t partial to one character’s lens throughout. In case the legitimacy of their bond was not apparent enough, actors Saleh Bakri and Mohammed Bakri are father and son in real life, adding a layer of complexity and realism to the script assigned to them. Jacir said it presented a little bit of hesitation on her part. “In Wajib, they have to be naked. They really have to be naked to do this together; to be open to confronting each other.” In the end, the duo pulled it off like clockwork.

Finally, Jacir promoted the future of Palestinian cinema. “I think there’s a lot of young people making really interesting work, while working in difficult conditions...The only thing that’s gotten better is that digital filmmaking has made things a little bit cheaper. You can make work and you can experiment more. Film is more accessible; making films is more accessible to people...I think there’s really more and more coming from Palestine – and it’s good stuff."

Although lesser known, this film has universal appeal and is extremely accessible. It is available on Amazon Prime. Her earlier features, When I Saw You (2012) and Salt of this Sea (2008) are streaming on Kanopy. Check it out!

Too Late to Die Young (2018)

Director: Dominga Sotomayor Castillo

Country: Chile

Good coming-of-age movies are few and far between, but when they manage to find the right combination of earnest performances and cinematic presentation, you are in for a real treat. This 2018 effort has the smooth, relaxed nature of Mia Hansen-Love’s Goodbye First Love without the specific focus on one woman’s arc, instead choosing to float between several members of the same community. Taking place in the insulated woodlands of rural Chile in the early 90s, we watch Sofia, Lucas, and Clara figure out which memories they wish to take from the limited realm of possibility, culminating in a fateful New Years Eve celebration that sends its characters spiraling in different directions.

The intended era clearly has a strong impact on the film’s look, with soft browns, reds, and greens catching the eye and making for a Thoreau-esque combination of nature, art, and angst. Each performance bears its own weight, but as the adults fall into line as the Charlie Brown parents backdrop, Demian Hernandez as the wide-eyed and impulsive Sofia steals the show. Additions of Mazzy Star’s Fade Into You (in both English and Spanish), cigarette smoke, and recurring imagery of a dog sprinting down a dirt road make for a truly atmospheric dip into outcast life.

Director Castillo became the first woman to win the Leopard for Best Direction at the Locarno Film Festival for this movie. Moveable Fest spoke to her in 2018 about her inspiration for the story. “There are some autobiographical elements in the film because I actually grew up in a community that is not exactly as it’s in the film, but [moved] to a place without electricity or phones when I was four years old and lived there for 20 years. Democracy was just arriving in Chile in the ‘90s and my parents and some friends decided to buy land that was cheap at the time, so they moved to this place and built their own houses.”

The political context is not something that is explicitly mentioned in the movie, but it might do better to know a bit about it: in 1973, socialist president Salvador Allende was overthrown by a coup d’etat. Military dictator Augusto Pinochet took over, both modernizing the country and committing many human rights violations. As time went on and the Cold War dwindled into Soviet Union democratic reforms, a plebiscite referendum was held in Chile in 1980 to create a new Constitution, with various modifications over time, becoming fully active in 1990 when the first peaceful transition of power was made in electing Democratic opposition Patricio Aylwin (more here) Some families saw this as an opportunity to reclaim their freedom and find independence where they could.

Regarding her multiple viewpoints, Castillo felt compelled to switch it up from the traditional setup.

…”I wanted a challenge of trying to make a [film from a] collective [point of view]. This is why I didn’t want to spend all the time with one character, but I wanted to jump into all these little stories...All the digressions and how there are no borders in the film is related to this image I had of there being no limitation between the interior and the exterior...There were no walls. There was not a clear separation between nature and humanity, feminine/masculine, kids or adults, so this was something that I wanted to explore.”

Castillo’s own mother serves as the casting director for her films, and in this particular case, they made the decision to cast kids without any experience from the locale, which meant a lot of them already knew one another. Her Sofia ended up being far different than what she had imagined, ultimately the perfect fit, as she found Demian “very complex… you cannot tell if she was young or old and it was a genderless feeling that I felt attracted to.” Hernandez began to transition soon after the film was complete.

Castillo relates her work to exercises in memory. “I think all my films have to do with this illusion of not forgetting. I have a very bad memory and always the starting point has to do with capturing something that is kind of blurry for me. This film was like capturing something that I was forgetting and that I wanted to remember.”

Too Late to Die Young is streaming on the Criterion Channel. Her earlier film, Thursday Till Sunday (2012), is streaming on Fandor.

And Then We Danced (2019)

Director: Levan Akin

Country: Georgia

Dance movies are, in my humble opinion, the backbone of the world. Physical expression of thoughts and feelings without the slightest need of a spoken word is poetic and significant, and in many ways a release of everything built up inside. I don’t need to tell you how exuberant the dance scenes in this movie made me feel, much less how anxious I was about the ill-fated romance at the core of the film- you just need to watch it yourself, and experience the plight of hard-working Georgian dancer Merab who can never quite find his footing.

However this wouldn’t be much of a recommendation if I didn’t at least mention the context of the film: Tbilisi, Georgia, modern day. Merab takes on the brunt of his family’s income, splitting his days between the National Georgian Ensemble and working as a waiter at a restaurant. He is in a semi-intimate relationship with his dance partner Mary. His brother is a drunkard but, given the requirements, a more desirably masculine dancer. When poised dancer Irakli arrives at the Ensemble, Merab finds himself experiencing a curious sort of attraction to this newcomer.

Levan Gelbakhiani is a sight to behold. With a face that’s hard to place but impossible to forget, he embodies the role of Merab with all his vulnerability, passion, and burden. His counterpart, Bachi Valashvili (who is a dead-ringer for Kit Harington), is charming, rugged, and simultaneously undetectable. His mystery makes for the provocative nature of the film’s first two acts, the rollercoaster of emotions Merab himself is feeling being identical to the ones that the audience is surely to experience.

Because of conservative Georgian politics, director Akin had to conduct filming in secret, which meant a lack of confidence in production locations. Says Akin to Mark Berger at Interview Magazine, “The whole experience of making this film was really different to me. Working in this way really gave the film its flavor. A lot of the ways the scenes are shot, with the angle of the camera and everything, were done out of necessity… We would lose locations on, like, a day’s notice. A lot of the scenes take place in the main dance studio, and we had another location, but two days before we’re going to start shooting, we lost it because they found out where we were doing.” Many of the actors in the film were either found on the street. Gelbakhiani, who plays Merab, was found through Instagram. Akin said they spent six months together so that when they were ready to shoot, Gelbakhiani would let the authenticity of that relationship shine through.

When the film was released, it received a polarizing reaction.

“In Georgia, we could only have three days of screenings because the rioters were so crazy. We had to have thirty policemen in every screening room, weapon detectors, and picket police outside. The protesters did a corridor of shame, they call it, so all the cinema viewers had walked through this shit. But they’re a loud mouth minority, because we also have so much support in Georgia. All the media outlets loved the film and supported it.”

Akin said the result has made a lot of progress in the country by bringing up conversations about sexuality. “It’s really leaped the dialogue of this topic ahead, like, 20 years. So much has happened in such a short time in Georgia because of this film. It’s crazy.”

Akin, who resides in Sweden, has plans for his next film about love set in Turkey and Georgia, set to release in 2022. Be on the lookout for Passage. And Then We Danced is streaming on Amazon Prime. This was one of my favorites of the challenge- check it out!

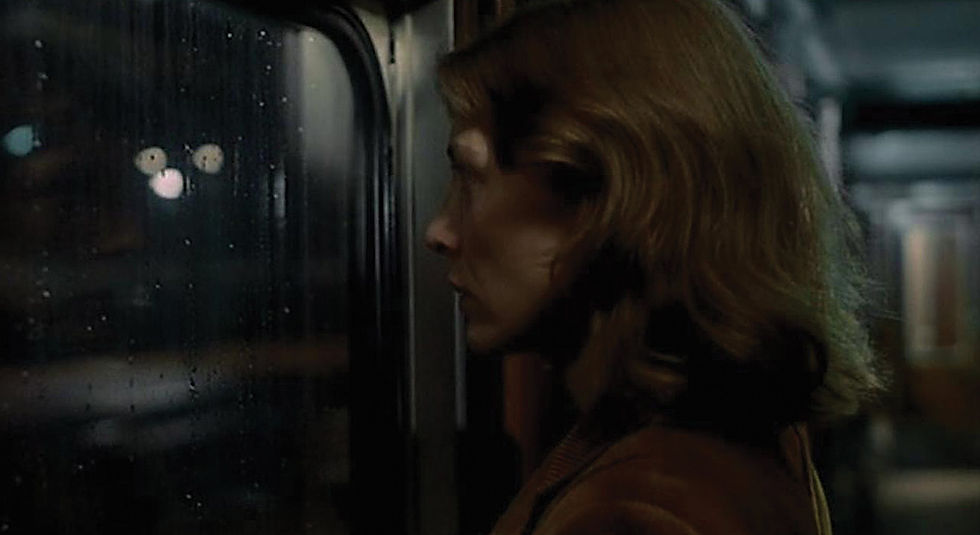

Les Rendez-vous d’Anna (1978)

Director: Chantal Akerman

Country: Belgium

Did I watch this movie primarily to dive into my Chantal Akerman box set I’d procured a couple months ago? Possibly. I said I was going to lean more into modern cinema with this project, but Akerman’s distinctive voice was something I was deeply curious about. By all standards, this movie’s restoration looks like it could’ve come out just a few years ago, so I stuck my ground, and watched the loneliest movie ever made.

Les Rendez-vous d’Anna follows Anna, a Belgian film director who moves from city to city each night for her work. She has various correspondences- ones that she links up with due to a past connection or one that she forms the night of so she doesn’t have to travel back to her hotel room alone. While the partners revel and share, Anna remains cold to most exchanges, aware she must be leaving the next morning, and that she is never truly at home.

“Loneliest Movie Ever Made” is a feat in its own, and I may be exaggerating the effect that this film had on me, but it’s difficult for me to drum up any other deep emotion that this made me feel. I watched this late at night, which is when the vast majority of the film takes place, and ultimately found myself feeling placid, forlorn, and pensive. Strangely, too, it made me appreciate the possibilities offered by social media and modern technology, as Anna might at least feel some degree of consistency through mutual connection. Akerman doesn’t move the camera much, allowing for the limited action to occur within the frame, a study of expressions and body language. Plenty of words and stories suggest a connotative purpose, but because of the condition in which they are heard, everything has a fuzzy white noise quality to it. The one exception to this rule is when we finally hear from Anna’s side while spending a night with her mother in Bruxelles. There, we learn of her affair with a woman, the one liaison Anna seems willing to actively pursue.

The movie was not well-received when it came out, due to many stark comparisons to Akerman’s earlier masterpiece Jeanne Dielman. Ultimately, there is very little interview or press-related information associated with this movie. Chantal Akerman passed away in 2015, leaving behind a great legacy of feminist films that made genuine ripples. Her films can be viewed streaming on the Criterion Channel.

Let the Right One In (2008)

Director: Tomas Alfredson

Country: Sweden

Vampire movies. Often undermined by the lesser interpretations (thanks, Twilight), many modern vampire tales don’t often see the light of day (haha) in discussion. What We Do in the Shadows (2014), Only Lovers Left Alive (2013), and Thirst (2009) are all special in their own ways. But Let the Right One In is probably the most cohesive, the most chilling, and strangely, the sweetest one of them all.

Alfredson’s film sets itself up in a snowy Stockholm neighborhood where people are mysteriously dying left and right. 12 year old Oscar is ruthlessly bullied at school, and dreams of ways to take down his torturers. Enter mysterious neighbor Eli, a young girl who only ever shows up at night, who gradually befriends him. It’s an interesting twist to establish a child’s perspective- although that doesn’t mean the film refrains from showing the blood and gore associated with this genre. The naivety of its protagonist is matched by the pervasiveness of its bleak circumstances. The looming threat is only amplified when the star-crossed duo finds themselves together, given Oskar’s still-unsophisticated thought process and Eli’s requisite volatility. It looks gorgeous, it’s frequently uncomfortable, and philosophically, it has a lot to say.

Finding the right Oskar and Eli required a lot of work. In an interview with Anthem Magazine, he shared the rigorous process. “It took a year to find Kåre and Lina. We don’t have professional child actors in Sweden, so we had to hold open castings. We went all over Sweden to find them...It was the hardest casting process I’ve ever been through.” Although children can be very loud, it was impertinent for the film’s tone that it concentrated on the less audible. Says Alfredson,

“You can work with silence to bring certain things across. If you fill the entire soundscape with effects, atmosphere and music, you can hide yourself as a filmmaker. But if you put up just one voice, one bird, or any one thing, you are being brave because you are saying something.”

Additionally, the silence was reflective of the stillness of the winter environment. It implores you to pay close attention to the slightest exchanges between characters, as it seems like every movement is a conscious effort. With deliberation, “You become very close to the children.”

Like any good thriller-romance with horror elements, Alfredson ties in a hearty dose of spookiness. “Fear works in your mind when you are imagining things... I think that a lot of entertainment today is a kind of monologue. I’m much more interested in having a dialogue with the audience and suggesting things to the viewers. You have a much stronger impact on the audience when they are active participants and you suggest things. The audience will make the worst images themselves.”

Let the Right One In is available on Hulu. Its original book, by John Ajvide Lindqvist, is considerably darker, and explores themes such as pedophilia, gentital mutilation, and alcoholism. Alfredson is most well-known in America for directing follow-up films Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011) and The Snowman (2017).

Vitalina Varela (2019)

Director: Pedro Costa

Country: Portugal

Pedro Costa is, from what I’ve heard, an acquired taste. Like Apichatpong Weerasethakul, there is an experimental element to his filmmaking that requires patience, and also a large enough film screen to truly immerse yourself in the environment of the film. I knew it would be pretty- but I wasn’t exactly sure if it would evoke disrelish or pleasure.

To my disappointment, I had a similar reaction to this art film- a stylistic retelling of a Cape Verdean woman’s life- as I did Uncle Boonmee and Japon, a Carlos Reygadas film that drained the life out of me. I’m not the type to lie to you and pretend that I enjoyed this. Besides the oil-painting like imagery, I found myself exhausted and tragically indifferent. The film transitions from the dark to the light, with some truly remarkable compositions in between, but I lost all value in the narration as one bleak, shadowy shot faded into the next.

That said- – my job here is not to invalidate anyone’s art, as there is clearly a large number of Costa fans who declare this to be his best one yet. Here’s what you might’ve gotten from it:

Vitalina Varela is a real woman, and she worked in close collaboration with Costa to get all the details right. Rather than the typical story beats of journey to destination, the film chooses to commence after Vitalina arrives in Lisbon, a tactical and tonal choice designed to enhance her feeling of loss when the audience discovers that her husband, who she has not seen in 25 years, died just three days earlier. Costa, interviewed by Michael Glover Smith at Cine-file in 2019, attributes that lonesomeness as the reason the film is, aside from flashbacks and a couple scenes towards the end, perpetually dark. Says Costa, ”Nobody knows her in the neighborhood, no one comforts her, everyone turns a suspicious eye… And this is where the film begins. Vitalina spends countless days and nights locked in Joaquim's shack. She barely survives the pain and the nightmares.”

To live one’s whole life in anticipation of an event that never comes to pass. Costa was skeptical the film would even work, due to the depth of Vitalina’s sorrow as she contributed to the scriptwriting process. But she persisted with her story, as did the crew in telling it.

Costa notes that some people are doomed from the start. There’s no way to create artificial happiness in order to take the place of their weariness. He explains,

“I can't give much to my Cape Verdean friends. I can't give them loads of money, I can't give them a bright future, I can't give them hope. But maybe there's everything to gain from our work in cinema. Cinema can set the record straight and, somehow, those who have been wronged will be avenged.”

The film gives a platform for a voice of grief and struggle. Costa’s work amplifies a sacred trend of filmmaking that looks beyond what’s desired by the masses and what’s easily digestible.

Vitalina Varela can be found on the Criterion Channel, as can his earlier films In Vanda’s Room (also HBO Max), Ossos, and Casa de Lava. I hope that you took the time to read through the positives and not disregard it completely just because it didn’t fit into my mold.

Manila in the Claws of Light (1975)

Director: Lino Brocka

Country: Philippines

We have arrived at the last film of the challenge: my first ever film from the Philippines. This movie is featured in Martin Scorcese’s World Cinema Project on the Criterion Channel as a compelling look at worker exploitation. I thoroughly enjoyed this and was reminded considerably of New Hollywood era American films such as The French Connection (1971) and Dog Day Afternoon (1975). Bembol Roco is truly great in a career-defining role that sees him challenge the pimps who took his lover into prostitution. The dialogue on its own is stark and powerful, but combined with Brocka’s keen eye for framing and Ike Jarlego Jr’s unique editing, the film deserves to be regarded as a true classic.

From 1972 to 1981, Ferdinand Marcos ruled the Philippines under martial law. He had been elected as President in 1965 as part of the Nationalist party, and was re-elected in 1969. Due to student protests and urban guerillas challenging his party, he asserted himself as dictator, and moved swiftly to imprison rival politicians and put down rebels. He even suspended habeas corpus for a time, giving him a reputation for corruption and economic stagnation. The guerilla movement continued, although now more dispersed among rural areas on the various islands. In many ways, this Manila in the Claws of Light is a time capsule of the poverty and disparity of the era, and very much a jab at the state of the government and its institutions.

Director Lino Brocka was, in many ways, a voice for change. Besides being known as one of the most influential Filipino filmmakers to date, he also fought against Marcos’ government as a member for the Coalition of the Restoration of Democracy and a co-founder of Concerned Artists of the Philippines (CAP). He was openly gay and made sure to incorporate the theme of sexuality into each of his films, as he did with the male prostitutes in Manila. He has received numerous accolades in the film world and has been honored in various Filipino establishments as a martyr for justice.

Manila in the Claws of Light is streaming on the Criterion Channel, as is Brocka’s film Insiang (1976). This is a really phenomenal movie that deserves to be known by more people, as should the name Lino Brocka. Check it out.

Sources:

That sums up our second 10/10/10 challenge. I am a bit weary of writing and may opt to do a couple of videos instead in the next few weeks (check out the new Youtube channel- I uploaded a Best First Watches of 2020 video to get it started). I hope you took away some recommendations and will send some more world cinema suggestions my way.

-Lydia

Kaiser OTC benefits provide members with discounts on over-the-counter medications, vitamins, and health essentials, promoting better health management and cost-effective wellness solutions.

Obituaries near me help you find recent death notices, providing information about funeral services, memorials, and tributes for loved ones in your area.

is traveluro legit? Many users have had mixed experiences with the platform, so it's important to read reviews and verify deals before booking.